A few weeks ago I had the opportunity to interview Adam Sargant, a Bard and dedicated storyteller who is actively engaged in both preserving and promoting the oral storytelling tradition on a community and wider level.

I’d watched Adam’s Marvellous, Magnificent Storytelling Machine and knew that he was working on a project on the use of trance in storytelling.

Below is an excerpt from Adam’s interview:

Who are you when you tell stories?

Adam explains that he sees himself as having a long line of storytellers behind him, his ‘lineage’, and that when he is getting himself into state for his storytelling he pauses and pictures those storytellers behind him, which is comforting. He also says that he becomes ‘Adam the Storyteller’ in that moment, so that storytelling itself is an identity for him, and it is important to him to be part of that lineage. Later, when we talk more about this moment of getting into state in which he connects with the lineage of storytellers behind him, he talks about how he empties out his ordinary, everyday self and everything attached, inviting his storytelling ancestors to lend their skill and inspiration and tell the story through him.

What’s important about telling stories?

Adam’s face gains more colour and he pauses, looking down and to the right, connecting to the question. Then he tells me about how storytelling is important for him as an outlet for his creativity, and that he believes that he can do it relatively well and make impact. He relates it to his identity and function as a Bard, and that not believing that he has poetic or musical skills (although, he lets slip, he does write poetry and plays musical instruments, he just doesn’t believe that he can do it for an audience), storytelling was really important for him to be able to pursue this path of personal development and to create himself as Adam the Storyteller, Adam the Bard.

What’s important about the stories?

Adam asks me whether I would like him to interpret this question as being about his choice of stories. I encourage him to share whatever has come to mind. He says that the stories he chooses must all match his values in some way. He then goes on to say that this is the purpose of stories – to pass on values, to pass on tradition. Later, we will talk about how much of a story is fluid.

What are you capable of when you are telling a story?

Adam tells me that at his best, he is able to transport the majority of his audience to the ‘as if’ place. The ‘as if’ place is a state of trance or an unconscious state, in which the listener is more aware of the story than of their own surroundings. This place is familiar to the avid reader of books, who can lose themselves in a story, and is also the place from which Adam likes to tell the story, so that he starts off by going into his own ‘as if’ place and then extending the reach of that place to bring his listeners in.

What do you need in an environment for you to tell a story?

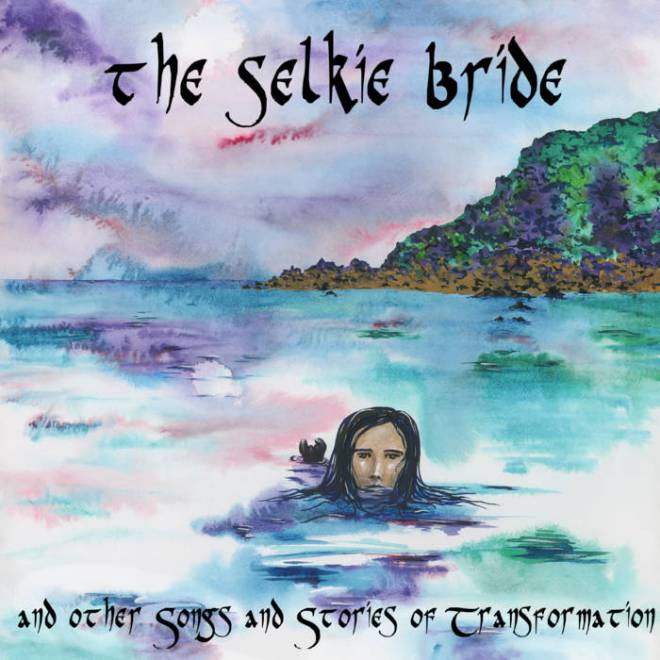

Adam says that it is important for him to be telling a story to real people, and goes on to describe how, when recording a story for mp3 (such as his recent Selkie Bride), he is ‘not talking to a microphone, but imagining people’. His eyes flicker upwards and he realises that the image he is using for this is of the pub where he usually tells his stories, and that the faces he sees are all ‘familiar’ – they may not be a particular person, he says, but they are definitely familiar, and that this image helps him to tell the story to the microphone.

I ask him how important familiarity is in the environment where he will tell a story, and he says that it is important but not essential. He tells the story of the first time he told a story in unfamiliar surroundings, as part of a workshop, and tells me that he just took an extra five minutes to get into state properly. We explore getting into state in some detail later on.

How do you engage the audience?

For Adam, this is very much about trance – about transporting his audience to that ‘as if’ space. So what he does is put himself into the ‘as if’ state first, and then extends it out to the audience. He says that he constantly calibrates the audience, both consciously and unconsciously, by looking at their facial expressions, breathing, looking and listening for responses to certain points in the story. He uses the example of me having smiled a couple of times when he was telling me the story of the Story-Needy Girl, and tells anecdotes of children jumping or drawing breath in in shock. He says that if he is not noticing any of these signals, he may then change his set list to another story which he hopes will engage the audience more.

How do you know which story to choose?

Adam explains to me that when he is learning a story, he ‘bare bones’ it – breaks it down to the most simple elements – and then cuts it down into chunks. This gives him a visual-spatial representation of the ‘shape’ and ‘pace’ of a story. He also has a visual idea of the emotion involved in a story, which he might represent as in a graph. When choosing a story after having calibrated an audience’s reaction to a previous story, he will choose a story to match or mismatch the shape, pace, and emotion of a story as appropriate.

How do you embody the story?

Adam talks about how he will reach for or point to an object or person to match the action in the story. He is very clear that he is a story-teller not an actor, and that it is not his intention to take up the space or call a lot of attention to himself, but to transport the listener to a space where they can create and experience the stories for themselves.

I ask him about how he puts himself into the state of the character who is speaking, and he talks about changing his tonality, facial expression and positioning. I ask him how he knows when to do this and he says that he has an image of the scene in front of him, from third position, and that when it is time for a character to speak or act he goes into first position from the point of view of the character, and gets the state and behaviours from there.

How much of a story can be changed as appropriate, and how do you know when it is appropriate to do so?

Adam proceeds to tell the story of The Story-Needy Girl, a little girl who needs to hear stories, and whose three nursemaids collect them for her. Each time the girl is given a story she puts it away in her bag, until one day her bag becomes so heavy that she puts it down while she goes out. The three nursemaids hear a whispering coming from the bag, and go and listen to it. Three stories are conspiring as to how they will harm the girl when she gets back. The girl returns and the three nursemaids protect her from the stories. The girl learns that she must let the stories go free, as an untold story becomes toxic.

Adam explains that he has adapted this story from a Korean folktale, in which the story-needy girl is a young boy, and the nursemaids are something else again, in order to fit it into his own cultural context, to assign meaning and authenticity when he tells it. He adds that he does tell some stories from other cultures, as long as they fit in with his values or can be adapted to fit his values.

Adam says that The Story-Needy Girl boils down to three key points which must be included – that the girl must collect stories, that the stories must plan to harm the girl, and that the girl must survive to discover that stories must be told if they are not to become toxic. This last truth, he says, is the purpose of the story, and any retelling must emphasise this. However, apart from this, any other elements of the story can be changed in order to ‘make it your own’ – from the words to the actors to the setting.

As to how he knows when it is appropriate to do so, Adam says that in this case it was about ease of telling and authenticity, but he will often change stories to match his values, and mentions anti-Semitism in Grimm’s fairy tales, which he removes when he retells the tales. I ask him about how closely a story must match his values, and he says that there is some room for manoeuvre – for example, when he tells the Mabinogion, which was written down in medieval times, he does not change it, because he feels that the length of time behind it and the way it is written make it too solid to change. However, he does not necessarily agree with its treatment of women (the Mabinogion was written in medieval times), and so always adds in an explanation of the structure of society in the times in which it was set when he is telling part of it.

You can buy Adam’s The Selkie Bride and Other Songs and Stories of Transformation here.

Meanwhile, as the storytelling model shapes itself, I’ve been interviewing Jan about her processes. I was excited to find that both she and Adam discovered, during the interview process, important elements in their storytelling, and that these elements were surprisingly similar. No more now until the model is complete, but suffice it to say that a model in common – despite the different storytelling contexts – is definitely there.